This review of SHOCK DOCTRINE originally appeared in the April 2008 issue of Vermont Woman under my byline At the end of my review here, you’ll find links to Naomi Klein and her views on economics since publication, and a video of her if you haven’t got time to read her astonishing book.

Canadian writer Naomi Klein strikes lightening at dark corners of contemporary U.S. history with her new book, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. Her work, while not easy to read, brings cathartic relief. She makes terrible sense of the worst pictures of recent America: the Twin Towers, Abu Ghraib and New Orleans’ Katrina. She lights images flashed world-wide over the past generation, ranging from the fall of East Germany’s wall to Tiananmen Square, from Walesa’s solidarity vault over a fence in Poland to the overthrow of Russia’s “White House,” from the end of apartheid in South Africa to Africa’s impoverishment.

All have economic bullying in common, an element seldom reported. Klein connects the dots between “free-market” economics and a foreign policy underpinned by the CIA and outsourced military forces, both of which exploit poverty to guard global financial interests, joining terror with yet more terror.

If this begins to sound like a conspiracy theory-it is. But it’s one the perps themselves acknowledge. These are the men who manage international trade, leverage currencies and develop economic policies of governments world-wide. They meet in the cabinet backrooms of presidencies and dictatorships around the world and apply pressure from The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to enforce private takeovers world-wide. Klein follows this fraternity’s mind-meld, dancing in their macro-economic circles.

Klein’s tale reads like a mystery, linking two influential thinkers: the first an American psychiatrist, and the other, an economist, both with grandiose views of humanity’s need for their radical makeovers. Both were “professionals,” who used remarkably ruthless means.

Klein begins the tale with a cold war scenario close to Vermont. Former president of the American Psychiatric Association, Ewen Cameron, began experiments in the late 1950s. His institute, associated with McGill University in Montreal, sought to remake human personality, wiping the slate clean to recreate a new, improved person. An epigraph from Orwell’s 1984 aptly describes his aim, which was funded by the CIA. “We shall squeeze you empty, and then we shall fill you with ourselves.”

Cameron used electric shock methods, but far more intensely than his peers. He combined this with sensory deprivation to prevent patients from knowing time or space, as well as hallucinatory drugs, disruption of sleep patterns, messages played over and over, loud noises or padded silences. Patients were stripped of clothing or any reminders of identity and memory.

They and their families had no idea Cameron was experimenting on them. His patients “regressed” to a dependent and malleable state, transformed into frightened children. They suffered terrible long-term harm and trauma-induced physical symptoms. By the 1970s, patients and their families had exposed Cameron’s secret and brought a lawsuit against the CIA. News in the Canadian press, this case was aided by the Canadian government and finally settled by the CIA, quietly, in 1988.

The CIA got their money’s worth. Cameron’s methods became part of the agency’s KuBark manual for interrogation, which is still in use. It ultimately found its way to military training facilities and to Abu Ghraib. Wherever KuBark went, electrical wires and psychological shocks showed up.

Meanwhile in another realm, a “free-market” economist named Milton Friedman, sought to wipe more slates clean, this time to remake economics. Friedman preached one idea for over 30 years: “Only a crisis-actual or perceived-produces real change.” He called his economic strategies “shock treatments.”

Friedman’s methods also called for quick jolts, rapid-fire transformation: tax cuts, no-holds-barred “free trade” for international corporations, privatized contracts to replace government functions, cuts to social spending, deregulation, and increases in military budgets. The last was essential. A charismatic teacher, Friedman ultimately headed the economics department of the University of Chicago and charmed an elite male following. His students included Donald Rumsfeld, who twice became Secretary of Defense, both times under Presidents Bush. Rumsfeld called his strategy for the Iraq war, “Shock and Awe.”

Friedman’s followers called themselves “The Chicago Boys.” Like Cameron and the CIA, Friedmanites were comfortable with erasing identities, even national ones, to remake the world in their image. Economic shocks administered by governments they counseled commonly roused terror in the public, resulting in a regression similar to the patients in Cameron’s care. Strip a nation of business-as-usual, its currency, its livable livelihoods, and people regress, becoming fearful, more malleable.

Klein doesn’t say this, but I was struck by their nickname for themselves in the context of coming to power in the 1970s. The Chicago Boys seems an affectionate nickname, until you remember women’s protests of the good-old-boys-network in those days and the male-only clubiness that patronized women-as-children. Collectively American women were making grown-up demands. They wanted to be involved in economic decisions that affected their lives. They wanted a social safety net, child care and maternity leave, and government involvement in alleviating women’s poverty.

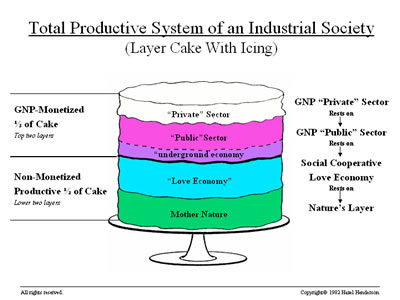

The leading economist back then, the one Friedman eventually displaced, John Kenneth Galbraith, was a Keynesian mixed-economist, who thought government should take an active role in the economy. Galbraith encouraged Marilyn Waring’s important economic critique: Who Counts: Economics as if Women Mattered. She argued reproductive and caring work of family and community, as well as Mother earth’s work reproducing clean water and air, needed to be included in our GNP (Gross National Product). It wasn’t. It still isn’t. Macro-economists use a national accounting system that counts weapons-making an economic plus, while weapons-use and war’s destruction never counts as a minus. Wasn’t this insane, Waring asked?

The Chicago Boy’s economic methods eschewed all such questions. Weapons contracts and weapons-use became the baseline of their operations. When Friedman had his first opportunity to apply his economic shock treatments in 1975, it was no accident it happened in Latin America, where mixed economies had been thriving, though resisting U.S. control Who was Friedman’s first client? A military dictator named Pinochet, who had overthrown the elected President.

Friedman’s work in Chile erased economic protections and compounded the misery of Pinochet’s prisons. Yet Klein notes this first project of his was barely mentioned in any of the obituaries lauding his reputation when Friedman died in 2006. More Latin American writers understood Friedman’s “Chicago Revolution” went hand-in-glove with the torture of protesters and their “disappearances,” and administered first in Chile, then in Argentina, Bolivia, Uruguay, Brazil and Guatemala. As Claudia Acuna, an Argentine journalist, told Klein, “Their human rights violations were so outrageous, so incredible, that stopping them became the priority. But while we were able to destroy the secret torture centers, what we couldn’t destroy was the economic program the military started and continues to this day.”

Thirty years later, Iraq would fall to a similar two-pronged shock, military and economic. I won’t attempt to describe here those more recent events but instead urge you to read the economic details yourself.

Friedman ultimately led Reaganomics’ trickle-down theories. His free-market ideology was revered by both Bush presidencies and influenced Bill Clinton in between. It’s worse than ironic that Friedman won the Nobel Prize in economics the same year that Amnesty International won it for their work with growing numbers of the tortured. Only a few witness-writers linked the economic violence of The Chicago Boys with government killing and jailing, but the result was a “free” market enjoyed by only a few, coupled with terror for the many.

“Torture is sickening,” Klein admits, wishing she hadn’t found this connection. “It is often a highly rational way to achieve a specific goal; indeed, it may be the only way to achieve it,” the reason robbers carry guns, she remarks. Klein’s shocking claims are made the more shocking by her careful documentation.

For the Chicago Boys, elections serve as useful distractions, whatever the political theater, wherever the country, as long as economic decisions about peoples’ fates get decided by their decidedly small group. That group continues to be dominant in the global economy, having evolved to become “The Washington Consensus.” Friedman’s free-market ideologues refined their method of moving in quickly on crises and human misery, finding opportunities for shock treatments and radical change. Simply translated, their methods transferred enormous national treasuries, and the decisions about it, from the many to the few.

Near the end of his life, when Katrina had wiped out New Orleans’ infrastructure, Friedman quickly proposed (and George W. Bush quickly funded) millions of dollars be used to replace the city’s public schools with privately run “charter schools.” To Friedman, a state-run school system reeked of socialism and its overthrow was a good thing. It is highly doubtful, however, such a clean wipe of the slate for New Orleans’ schools would ever have happened in any open, democratic debate. Shocks, like Katrina and a FEMA that showed up too late, and too little, overwhelmed state and local governments to compliancy.

The Chicago Boys’ record, the Washington Consensus and its record, the global policies of the IMF and the World Bank and its statistics, all show us a world where growing numbers grow poorer and a very few grow very rich. Yet Klein ultimately ends her book on a positive note. World-wide, there’s growing resistance to the free-market’s shocks, a reason for us to hope for a better future-but only if we hold American bully-boys accountable, and only if we educate ourselves about our nation’s budget and policies.

http://www.naomiklein.org/shock-doctrine